CSYE Glosses

Ni(sh)to – far vos?

Exploring the Geography of Negation (Part 2)

In my previous post on the topic of ני(ש)ט ni(sh)t, I included a map based on CSYE data showing the geographic distribution of these two forms of the negative particle in Yiddish. Rather than being a north-south distinction, as one might think, it is more of an east-west one, with a fairly stark dividing line running from between Warsaw and Białystok, heading south-southwest toward the old Volhynia/Galicia border, and thence through what is now Moldova, where there seems to be a bit of a transitional area. The northern part of this line is a familiar one; it follows the edge of Northeastern (Litvish) Yiddish fairly closely, although one survivor (Bracha Shumowitz) from near Lomzhe (Łomża), just inside the Northeastern Yiddish border, uses nisht 98% of the time, despite speaking unmistakably Northeastern Yiddish. But at a certain point the nit/nisht line departs from the Northeastern Yiddish boundary and continues southward.

This southern part of the line shows up in Yiddish dialectology for other features. It is roughly the same line that delimits the western edge of the pronunciation /oy/ in words like פֿרױ froy (to the west it’s pronounced /fruu/ or /frou/). Interestingly, it bisects the Southeastern Yiddish dialect area roughly in half. Yiddish vowel systems have their own internal logic, with shifts in one vowel contributing to additional shifts in other vowels. (These are called chain shifts, and they are common in Germanic languages, which tend to have more vowels than other languages.) So it could just be a coincidence that the southern part of the nit/nisht line loosely corresponds to the froy/fruu line. Or it could be that there is some real dialect cleft here, one obscured by the fact that it runs through the middle of a generally accepted dialect area (Southeastern Yiddish).

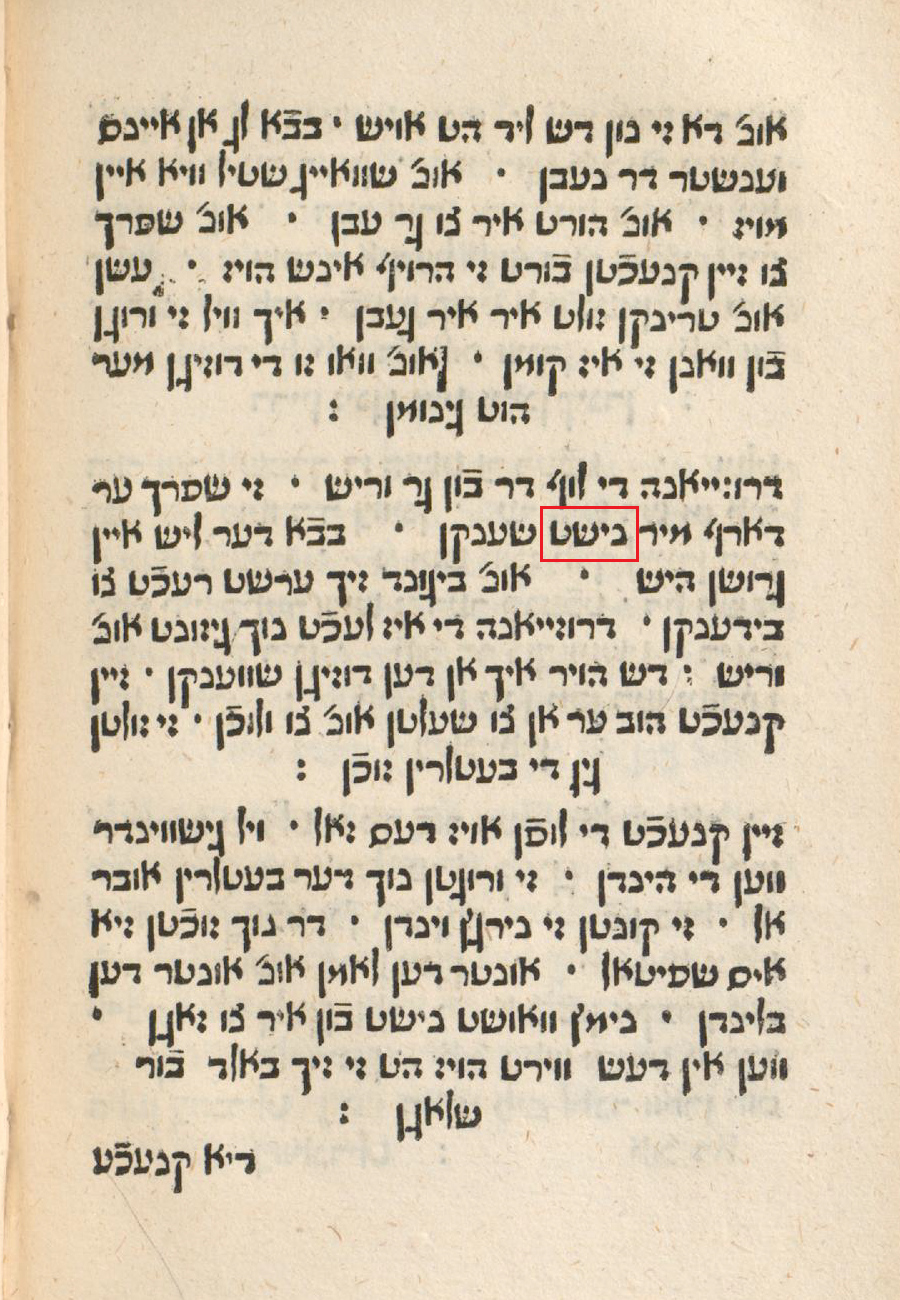

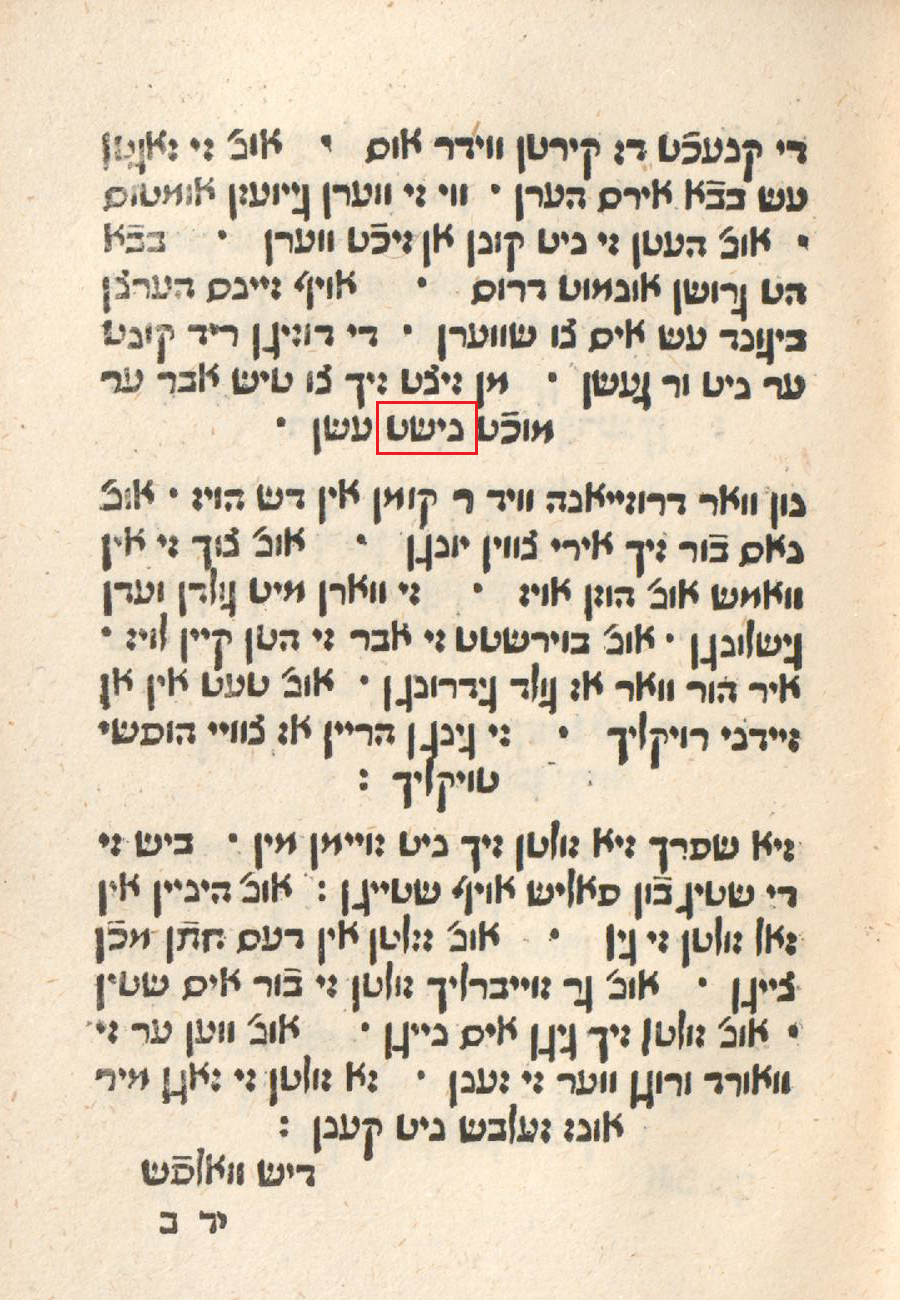

In any case, I also noted in my last post that even though nisht is clearly the newer form, it can still be found in some of the earliest printed Yiddish books. Figure 1 shows nisht in the 1541 first edition of Elye Bokher’s Bove-bukh, appearing on two consecutive pages.1 This book, whose publication in Isny im Allgäu (southern Germany) was overseen by the author himself, was originally composed in 1507. And nisht can even be found in manuscripts that predate Yiddish printing, such as the anonymous Seyder noshim, a manuscript that was written in 1504.2 So while nisht may be an innovation, it is hardly new.

Gornisht mit nit

One interesting fact that the corpus reveals is that the distribution of גאָרנישט gornisht ‘nothing’ is wider than that of נישט nisht, as shown in Figure 2. A significant number of speakers use gornisht predominantly, or even exclusively, deep in what is otherwise nit territory in the north, especially in present-day Belarus. It is hard to know why this is. Did gornisht replace gornit in this region? Or could it be that nit replaced nisht, but left gornisht as a remnant? The latter seems less likely, given that we can presume nit is the conservative form. Perhaps a key to this small mystery is the fact that gorni(sh)t is itself a newer development. In older Yiddish texts one can occasionally find “gor nit/nisht” (with a space), but in the sense of ‘not at all’ rather than ‘nothing’;3 the older Yiddish word for ‘nothing’ is niks, cognate with German nichts. Eventually gorni(sh)t replaced niks, at least in Eastern Yiddish, and one could imagine that it arose initially as gornisht in nisht territory, spread throughout Eastern Yiddish, and was partially renormed to gornit in the areas where nit predominated. But this is just speculation.

Ni(sh)to keyn /nitu/

Another interesting case is the word ני(ש)טאָ ni(sh)to, used in the present-tense negative existential construction. Like gorni(sh)t, this doesn’t match the distribution of nit/nisht. In fact, nito/nishto follows the division between Northeastern (Litvish) Yiddish and the rest of Eastern Yiddish, just as nit/nisht is popularly but inaccurately thought to do. This is just as puzzling as the presence of gornisht in nit territory. The word, meaning ‘[there is] no,’ arose as a contraction of ni(sh)t and do ‘here.’ Why should speakers in the eastern part of Southeastern Yiddish say nit but also nishto? It is worth noting that the boundary between Northeastern and Southeastern Yiddish is usually defined based on the pronunciation of the second vowel in ni(sh)to (and other words with this vowel): it is /o/ north of this line and /u/ south of it. So perhaps there is simply some sort of resistance to the form /nitu/, resulting in nishto (which, it should be noted, is pronounced as “nishtu” in the dialects where this is the predominant form) extending into the same Southeastern Yiddish territory that has nit. Or perhaps this is circular reasoning (the reason people don’t say /nitu/ is because one simply doesn’t say /nitu/?).

Nokh ni(sh)t…

The presence of gornisht in Northeastern Yiddish and of nishto in the nit area of Southeastern Yiddish raises interesting questions. Are these survivals or intrusions? At this point it is hard to know. The speakers in our corpus who use nit predominantly are more likely to have a few instances of nisht than vice versa, which suggests that nisht was on the rise, although this could also be the result of postwar contact with other dialects. All in all, thanks to the CSYE, we know more now about the distribution of ni(sh)t, gorni(sh)t, and ni(sh)to than before, but we also have more questions. Now the real research can begin.

Notes and References

-

The book is available to download from the Zentralbibliothek Zürich. The images in Figure 1 come from pp. 215–216 (according to the page numbering in the PDF). ↩

-

An excerpt is available in Jerold C. Frakes (ed.), Early Yiddish Texts, 1100–1750: With Introduction and Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 115–119. The excerpt also includes nit. ↩

-

The phrase gor nisht (with a space) to mean ‘not in the least, not at all’ has also been prescribed for contemporary Standard Yiddish. See Mordkhe Schaechter, Yidish tsvey: A lernbukh far mitndike un vaythalters [Yiddish II: An intermediate and advanced textbook], revised ed. (New York: League for Yiddish, 1995), 174. ↩

Cite this article

- Sadock, Benjamin. 2025. "Ni(sh)to – far vos?: Exploring the Geography of Negation (Part 2)." In Isaac L. Bleaman (ed.), Corpus of Spoken Yiddish in Europe (CSYE) Glosses, https://www.yiddishcorpus.org/csye/glosses/nishto-far-vos. Accessed .

-

@InCollection{Sadock-2025, author = {Benjamin Sadock}, booktitle = {Corpus of {Spoken} {Yiddish} in {Europe} ({CSYE}) {Glosses}}, editor = {Isaac L. Bleaman}, title = {Ni(sh)to -- far vos?: Exploring the Geography of Negation (Part 2)}, url = {https://www.yiddishcorpus.org/csye/glosses/nishto-far-vos}, urldate = {}, year = {2025} }

© Benjamin Sadock, 2025. This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.