CSYE Glosses

Far vos ni(sh)t?

Exploring the Geography of Negation

My first Yiddish teacher, the linguist Howie Aronson z”l, once told me an anecdote about a Yiddish editor (he couldn’t remember who) who was supposedly the last person to understand the distinction between ניט nit and ניטש nisht. This presumes that there was some subtle nuance between the two forms of the Yiddish negative particle (meaning ‘not’), and skilled users of the language were formerly able to navigate between these forms. But this premise clashes with the prevailing understanding of the distribution of the forms, namely, that this is a geographic distinction — a matter of dialect, not semantics. I had heard it generally said that nit was the Litvish (Northeastern Yiddish) form. So what is the distinction: geography or meaning? And how did Yiddish arrive at these two forms?

Let’s examine the second question first. Max Weinreich’s History of the Yiddish Language, often so helpful with issues like this, has the following to say: “nisht… is a problem in itself.”1 One wishes he had said more. Alexander Beider sheds a little more light on things: “In Ashkenazic sources, forms [of ‘not’] without /x/ and /h/ [i.e., nit] have been standard in all regions since the Middle Ages…”2 In other words, nit is the older form. Whence nisht then? The “sh” provides a clue: this is clearly ich-laut, a sound change that occurred in Standard German along with many German dialects that changed the “ch” sound to something like a “sh.” Notably, there is no ich-laut in the Germanic component of Yiddish, which is why the word for ‘correct’ is ריכטיק rikhtik, not רישטיק rishtik. So it seems safe to say that not only is nit the original form, but nisht phonetically reveals itself to be a later borrowing from German (although I was able to find instances of nisht in Yiddish books going back to the sixteenth century). Perhaps this is why Weinreich called this form “a problem in itself”: according to his Yiddishist viewpoint, Yiddish was autonomous of German in the early modern era, making such a borrowing hard to explain.

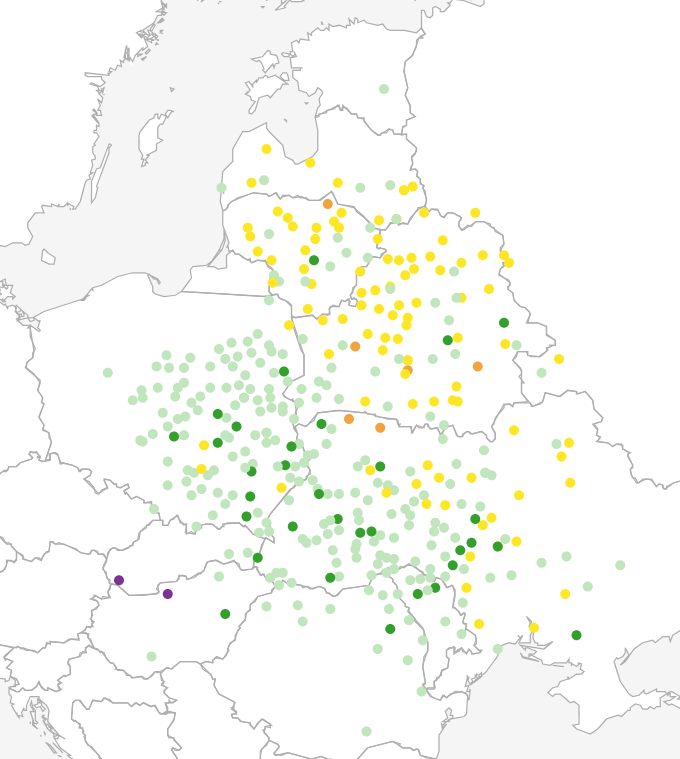

So what about the distribution of the two forms? Is it geographic, or are they overlapping, allowing for the language to express different nuances in choosing between the two? Lea Schäfer is a linguist who uses cutting-edge dialectrometry to analyze Yiddish geographically, drawing on the written fieldnotes produced for the Language and Culture Archive of Ashkenazic Jewry. She has created an online browser that allows users to generate maps based on this data source. Here is the map for nit/nisht:

There appears to be some overlap between the two main variants, nit (in yellow) and nish(t) (in shades of green), but also a fairly obvious geographic pattern: nit predominates in the eastern part of Eastern Yiddish and nisht in the western part. But while Schäfer’s methods (which are not actually involved in the creation of this particular map) are advanced, the data source is not ideal here. Each of these points represents a single response for each LCAAJ informant, specifically the answer to the prompt to translate the English sentence “They don’t speak German” (or Hebrew: “הם לא מדברים גרמנית”) into Yiddish. Having listened to recordings of these interviews, I can say that many informants were very confused by this task and thought they were being asked about their own German proficiency or that of their Jewish and/or non-Jewish neighbors. And this single, often confused, always self-conscious response was the sole data point for each speaker for this map, which means that if a speaker used both forms, the map couldn’t reflect that. Moreover, the form they used in that moment might not be the one they used more often. So the data itself isn’t great, which is perhaps why the map looks so noisy. A better data source would be free, natural speech, with multiple instances of nit/nisht per speaker. Fortunately, the Corpus of Spoken Yiddish in Europe provides just that.

I searched through the transcripts for the 130 Holocaust survivors whose testimony has been at least partly transcribed so far. Instantly I was able to see that for these speakers, one form or the other always predominated. In fact, 43 speakers used nisht exclusively, and 24 used nit exclusively. Furthermore, of those who used both forms, 17 used nisht over 99% of the time, and 16 used nit over 99% of the time. So 100 of the 130, or 77%, used one form or the other exclusively or almost exclusively.

Looking deeper, 12 used nit over 95% of the time, and 5 used nisht over 95% of the time. Indeed, only 8 speakers used one form or the other under 90% of the time, and two of them are outliers: speakers from otherwise overwhelmingly nit regions who seem to have picked up nisht (presumably postwar) as an affectation. Aside from those two anomalies, we find that 122 out of 128 speakers used either nit or nisht over 90% of the time, and that the most any speaker used their less-used form was 24%. So whether or not there was at some point a nuanced difference of meaning between the two, there certainly wasn’t much room for one by the twentieth century, when Eastern European speakers of Yiddish had overwhelmingly settled on one form or the other.

Now that we’ve extracted this data from the CSYE transcripts, let’s map it using the speakers’ birthplaces. Here’s the result:

We see the same east/west division as in Schäfer’s LCAAJ questionnaire map, but much more clearly. Nit predominates throughout Northeastern Yiddish, plus the eastern part of Southeastern Yiddish; nisht predominates in Central Yiddish, as well as the westernmost part of Southeastern Yiddish. There is also a transitional area in the south, around Bessarabia (roughly, modern Moldova).

This very simple exercise in data mapping shows the promise of the CSYE to shed new light on prewar European Yiddish. And as more tapes are transcribed and more survivors are added, the data will only become more robust.

So what else can we learn from the CSYE about nit and nisht? And what about words derived from them, like gorni(sh)t and ni(sh)to? I will turn to these questions in my next Glosses post.

Notes and References

Cite this article

- Sadock, Benjamin. 2025. "Far vos ni(sh)t?: Exploring the Geography of Negation." In Isaac L. Bleaman (ed.), Corpus of Spoken Yiddish in Europe (CSYE) Glosses, https://www.yiddishcorpus.org/csye/glosses/far-vos-nisht. Accessed .

-

@InCollection{Sadock-2025, author = {Benjamin Sadock}, booktitle = {Corpus of {Spoken} {Yiddish} in {Europe} ({CSYE}) {Glosses}}, editor = {Isaac L. Bleaman}, title = {Far vos ni(sh)t?: Exploring the Geography of Negation}, url = {https://www.yiddishcorpus.org/csye/glosses/far-vos-nisht}, urldate = {}, year = {2025} }

© Benjamin Sadock, 2025. This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.